Endereço

304 Norte Cardinal

St. Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Horas de trabalho

Segunda-feira a sexta-feira: 7h - 19h

Fim de semana: 10:00 - 17:00

Endereço

304 Norte Cardinal

St. Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Horas de trabalho

Segunda-feira a sexta-feira: 7h - 19h

Fim de semana: 10:00 - 17:00

In the world of metal fabrication, achieving the perfect curve without compromising structural integrity is an engineering challenge. Aluminum profile stretch bending stands out as a premier cold-forming process, essential for industries ranging from aerospace and high-speed rail to architectural curtain walls.

Unlike standard bending methods, stretch bending offers unparalleled stability for thin-walled profiles and complex geometries. This article provides an in-depth analysis of the technical characteristics, operational precautions, and advanced simulation methods used to master aluminum profile stretch bending.

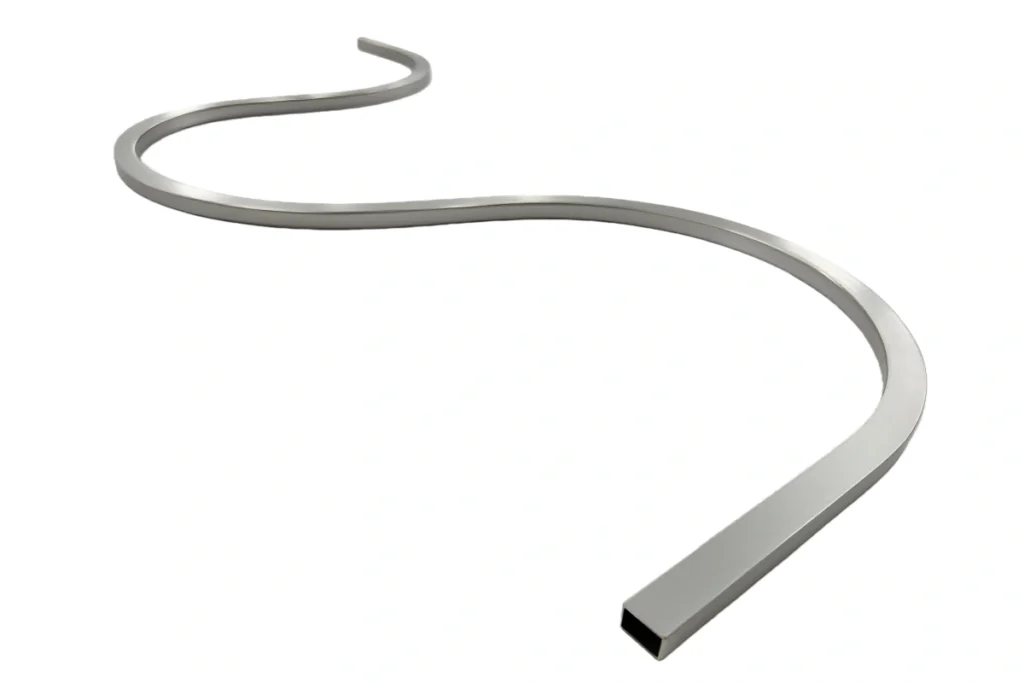

Aluminum profile stretch bending is a cold-forming process where an aluminum extrusion is placed under tension and simultaneously wrapped around a die (form block) to create a specific radius or contour.

During the process, the profile is gripped at both ends by hydraulic jaws. These jaws apply a longitudinal tensile force that exceeds the material’s yield strength but stays below its ultimate tensile strength. While under tension, the profile is bent over a mold. This combination of stretching and bending minimizes common defects like wrinkling on the inner radius and reduces elastic springback.

To optimize production, it is vital to understand the unique constraints and behaviors of this technology.

Standard stretch bending equipment is typically designed for bends of 180° or less. Unlike roll bending (rotary bending), which can produce continuous coils or circles (360°+), stretch bending is linear-to-arc. While specialized rotary stretch-bending machines exist, they are rare and used for niche industrial applications.

In stretch bending, the “neutral layer” (the area of the profile that remains at its original length) is theoretically shifted toward the inner surface of the bend. Consequently, nearly the entire cross-section of the profile undergoes extension. This means the finished part will always be slightly longer than the original raw extrusion.

A defining feature of this process is the necessity of clamping margins. Because the hydraulic jaws must grip the profile securely to apply tension, a portion of the material at both ends will be deformed or “marked” by the jaws. This material is considered waste and must be trimmed after forming, unlike roll bending where waste is minimal.

Stretch bending is not suitable for extremely tight radii. If the required radius is too small, the outer fibers of the aluminum will exceed their elongation limit, leading to fracture or wall thinning. For sharp corners, other methods like press bending or V-notching are preferred.

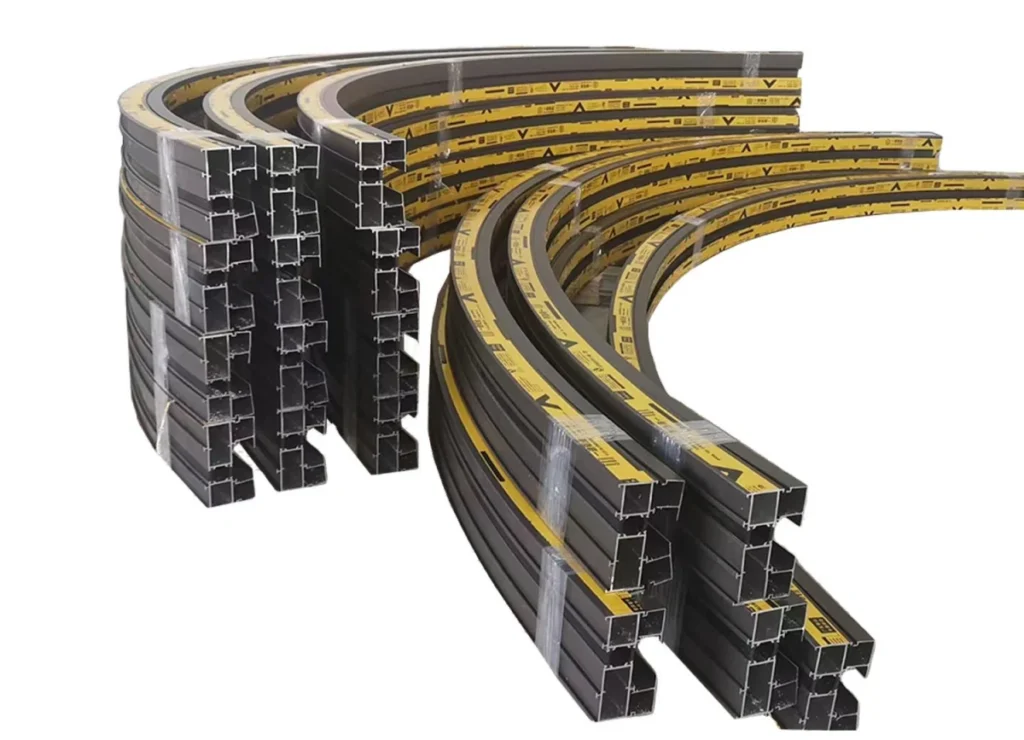

Interestingly, in some international markets, roll bending is more prevalent for high-volume commercial goods due to its speed. However, for high-precision aerospace and structural architectural components, stretch bending remains the gold standard worldwide because of its superior cross-sectional control.

Precision in aluminum fabrication requires strict adherence to thermal and mechanical protocols.

Aluminum profiles should only be moved to the stretching frame once they have cooled to below 50°C.

The standard stretch rate should be maintained at approximately 1%.

To prevent deformation in complex shapes (such as “open” profiles, circular arcs, or cantilevered shapes), specialized filler blocks or protective pads must be used. These pads ensure that the clamping force is distributed evenly and that the profile’s hollow sections do not collapse under tension.

Special attention must be paid to profiles with high width-to-thickness ratios, long “legs,” or varying wall thicknesses. These “odd-shaped” profiles are susceptible to:

For high-end decorative aluminum, the profiles must be rotated and flipped during the cooling phase to ensure uniform heat dissipation. Uneven cooling can lead to “lateral bright spots” or crystalline inconsistencies, especially in wide or thick-walled profiles.

During picking, moving, and stretching, profiles must be kept apart. Friction between profiles can cause scratches or galling. For long or flexible extrusions, support bridges must be used to prevent sagging or accidental bending during transport.

Modern manufacturing relies on mathematical models to predict how aluminum will react during deformation.

Aluminum profiles are typically formed via extrusion, which offers stable quality but introduces specific internal stresses. Predicting the 3D stretch-bending trajectory is difficult because:

To simplify calculations, engineers use the Principle of Relative Motion. This involves transforming a dual-head stretch bending model into a single-clamp equivalent model. This reduction in variables allows for more accurate trajectory planning and reduces the computational load on simulation software.

Aluminum’s mechanical properties differ significantly from steel:

Research Insights on Springback:

Where do we see this technology in action?

Aluminum profile stretch bending is a marriage of heavy machinery and delicate precision. As industries move toward more complex, organic shapes—driven by both aesthetics in architecture and aerodynamics in transport—the demand for advanced stretch bending will grow.

By mastering the 1% stretch rate, controlling thermal cooling, and utilizing equivalent transformation simulations, manufacturers can produce flawless curved profiles that meet the most stringent engineering standards.

Q1: Why is stretch bending preferred over roll bending for architectural aluminum?

A: Stretch bending provides better control over the profile’s cross-section, preventing the hollow chambers of the extrusion from collapsing, which is critical for structural integrity in facades.

Q2: What is the typical scrap rate for stretch bending?

A: The physical scrap is usually limited to the grip ends (the “heads”). However, with poor temperature control, the scrap rate can increase due to twisting or surface defects.

Q3: Can 7075-T6 aluminum be stretch bent?

A: Yes, but it is much more challenging than the 6000 series. High-strength alloys like 7075 require precise tension control and often benefit from being bent in a “W” or “O” temper state before being aged to “T6.”

Keywords: Aluminum profile stretch bending, Cold bending process, Metal fabrication, Aluminum extrusion bending, Springback in aluminum, Industrial bending technology.